UFOs as Psychological Phenomenon

On Extraterrestrial Intelligence, Archetypes, and Psychedelic Ufology

Apparently, we are on the cusp of learning that the United States government has multiple extraterrestrial aircraft. Conspiracy theories about aliens and the US government are nothing new, but there is something different about this round of leaks and admissions. It’s a funny coincidence that the spike in UFO hysteria is occurring with a rise in psychedelic frenzy. Psychedelics are going mainstream, bolstered by decriminalization efforts across the US and the realization by pharmaceutical companies that they can make a lot of money synthesizing plant medicine compounds.

The absence of psychedelic ufology in the mainstream debate is notable, given the profound interest in these two fields. The basis of psychedelic ufology is found in Carl Jung’s fascinating work treating UFOs as a psychological phenomenon. Jung began to collect accounts of UFO sightings late in his life, which he published in 1959 as Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies. In the work, he sought to understand UFOs from an archetypal standpoint. He wasn’t concerned with whether they were real and didn’t mention psychedelics. In a 1957 letter to the New Republic, he wrote that UFOs were probably real. Jung was interested in UFOs as archetypes of the collective unconscious, and that’s what we will focus on here.

Archetypes and UFOs

Archetypes in Jungian psychology are universal symbols or patterns present in the collective unconscious we all share. They are innate and inherited but can shape our thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Dreams are the most fertile source of archetypes in the individual. They “have the advantage of being involuntary, spontaneous products of the unconscious psyche and are therefore pure products of nature not falsified by any conscious person.”

Jung’s argument was that the UFO was an archetype for our modern condition. In the 1950s, when UFO sightings became a facet of the popular imagination, Jung understood them as archetypes of our collective fears and psychic panic during the Cold War. It’s no coincidence that most UFO sightings occur at night, and many abduction claims happen when the person sleeps.

Think of a lone person chopping wood in a quiet forest, and a beam of light comes from the heavens. In the Middle Ages, Jesus would likely descend from the light. Today, it would be a UFO. This, for Jung, was a “redeeming supernatural event.” The academic Christopher Partridge puts the implication of these events into sharper focus: “Whereas earlier cultures would have considered intervention from heaven as a matter of course, in ostensibly secular societies, largely bereft of the mythic resources of the past, UFOs replace traditional deities as the agents of salvation.”

Jung himself noted that “we have indeed strayed far from the metaphysical certainties of the Middle Ages, but not so far that our historical and psychological background is empty of all metaphysical hope.” The metaphysical hope that we can’t escape from “activates an archetype that has always expressed order, deliverance, salvation, and wholeness” in a way that is “characteristic of our time.” The UFO, which can defy science and seemingly do anything, is the philosopher’s stone of medieval alchemy.

From an archetypal perspective, the reason for our UFO hysteria is the depth of our current cultural crisis. In the 1950s, when accounts of UFOs began proliferating in mainstream consciousness, the gravity of the Cold War and the threat of global nuclear annihilation weighed heavily on the collective unconscious. The message of the UFO for the philosopher of psychedelics Terence Mckenna (echoing Jung) was that “humanity needed to wake up and get its act together to avoid destroying the planet.”

Previous generations endured similar cultural crises but handled them differently. During the Renaissance, for example, there was a push to return to Roman and Greek times by adopting their roads, architecture and thought. As a drowning person grasps for the surface, culture reaches out to a previous cultural metaphor to stabilize itself. Our current crisis is too large for that, so we have looked for something outside history.

This is the Mushroom’s Program

Terence Mckenna was the most prominent thinker to popularize Jung’s ideas and marry them with psychedelics. One of the central tenets of Mckenna’s broad thinking about psychedelics and UFOs posits that psilocybin mushrooms are extraterrestrials and the powerful psychedelic DMT catapults users into a place occupied by aliens. With the correct dose of either substance, we can even converse with otherworldly entities. “DMT plunges us,” Terence Mckenna said late in his life, “not into our own unconscious, but into some sort of hyperspace or ‘interdimensional nexus’ with its own alien inhabitants.”

Influenced by the idea that life didn’t originate on Earth (instead, it arrived on this planet within comets, meteorites, and space dust), Mckenna famously argued that the mushroom itself was extraterrestrial. The “mushroom was somehow more than a plant hallucinogen or even a shamanic ally of the classic sort … The mushroom was, in fact, a kind of intelligent entity—not of earth—alien and able during the trance to communicate its personality as a presence in the inward-turned perceptions of its beholder.”

The idea of mushrooms coming from the great beyond and having a place in space travel isn’t entirely rejected by science. In recent years, mycologists like Paul Stamets have been building on this theory in reputable journals such as Scientific American to advocate for using mushrooms in space exploration.

Mckenna’s argument is radical in its simplicity. Not only have mushrooms come from outer space, but they also entered into a sort of unspoken covenant with humanity for mutual benefit. The mushroom gave us intelligence or the ability to become intelligent. Mckenna points to the rapid growth of the human brain – the fastest among any living being in Earth’s history – as evidence of this exchange.

When our early ancestors descended from the forests and began walking across the African savannah, they must have encountered heaps of psilocybin mushrooms, which they presumably ate in large quantities. According to Mckenna, the explosion of psychedelic imagery these experiences induced kickstarted the production of culture, language, and religious ideas. Current research into the effects of psilocybin demonstrates convincing evidence that the mushrooms open up new neural pathways and contribute to neuroplasticity, among other mind-expanding properties.

In the introduction to his psilocybin growing guide, Mckenna recounts one of his conversations with the mushroom while on a 5-gram hero’s dose. “I am older than thought in your species,” the mushroom told him. “Though I have been on Earth for ages, I am from the stars... You as an individual and Homo sapiens as a species are on the brink of the formation of a symbiotic relationship with my genetic material that will eventually carry humanity and the earth into the galactic mainstream of the higher civilizations...nature loves courage.”

UFO hysteria is hardwired into the consciousness of modern society. While there are plenty of genuinely far-out theories in the field of psychedelic ufology, the central idea that UFO sightings have something profound to do with our psychology is stimulating. As for the mushroom being an extraterrestrial, I am eager to ask it some questions the next time I find the courage to venture into hyperspace.

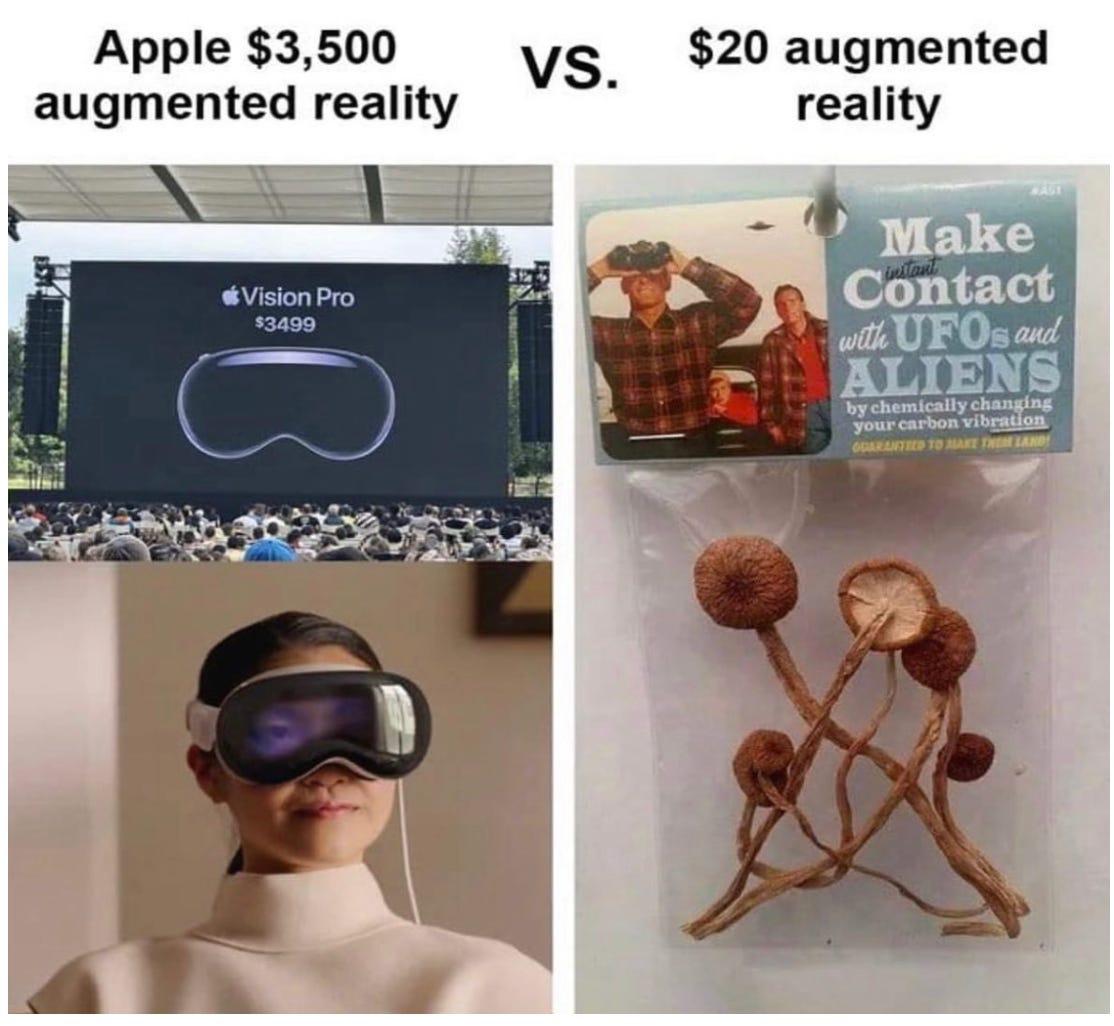

Yes, psilocybins > Goggles. But also we LOVE Jung's UFO book. So kooky.