False Messiahs, Then and Now

On Sabbatai Tzvi, the politics of messianism, and the quest for redemption

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has profoundly impacted our lives recently, hitting close to home as intense debates about Israel unfold among our family and friends. After dedicating many years to studying Jewish history and living in Israel and Palestine for over a decade, I find it increasingly challenging to witness how difficult it is for many to engage critically with something they deeply care about.

While I was working on a master’s degree at Hebrew University, I became engrossed in the story of Sabbatai Tzvi, the 17th-century figure proclaimed as the Jewish Messiah. This historical curiosity has recently proven invaluable. After finishing Yaacob Dweck’s compelling biography of Rabbi Jacob Sasportas, Tzvi's staunch critic at the time, I feel inspired to go deeper with the politics of messianism and today’s constrained dialogue about Israel. This week, we'll delve into the lives of Sabbatai Tzvi and Jacob Sasportas, exploring the past and present impact of false messianism on Jewish communities. A final note: This is a longer piece than usual, and the tone differs from the standard.

“One does not defeat a Messiah with common-sense arguments.” —Czeslaw Milosz

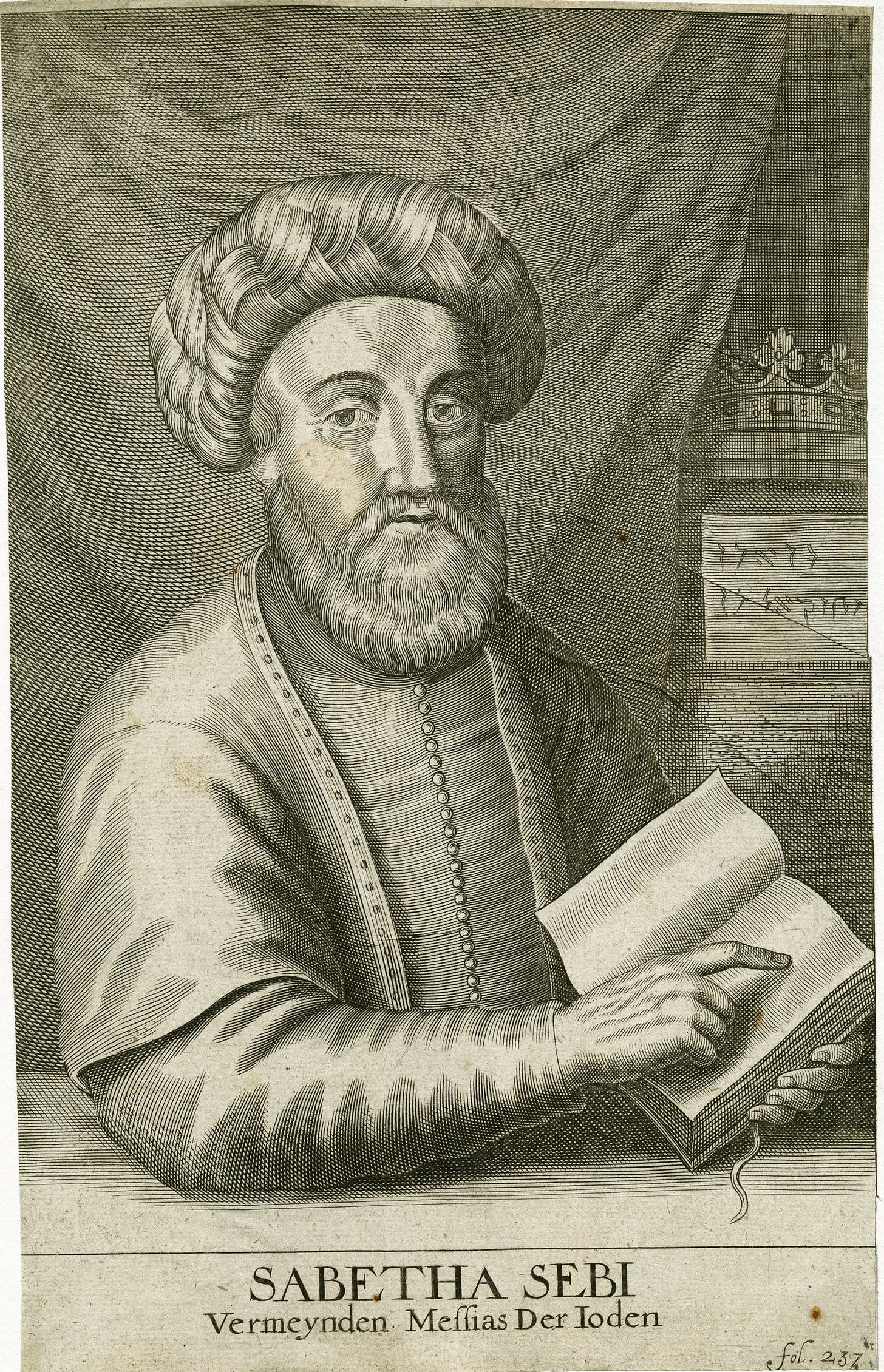

Sabbatai Tzvi was a 17th-century Sephardic rabbi who became the central figure of Jewish history's most influential messianic movement. Born in Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey) in 1626, he was charismatic, learned, and sometimes eccentric. He initially gained attention for his deep knowledge of Kabbalistic traditions and intense, mystical practices.

His followers proclaimed him the Messiah in 1665, which sparked a messianic fervor across the Jewish diaspora. Many Jews, disheartened by economic hardships, persecution, and their expulsion from Spain, were enthralled by the promise of redemption and rallied to his cause. The movement gained a wide following, from Europe to the Middle East and North Africa, thanks to the work of several prominent rabbis that legitimized Tzvi’s messianic credentials.

Chief among these rabbis was Nathan of Gaza, born Nathan Benjamin Levi in Jerusalem. He proclaimed Sabbatai Tzvi the Messiah after purportedly receiving a revelation. Nathan's intellectual prowess helped him to articulate and disseminate complex kabbalistic ideas that legitimized Sabbatai's messianic claims to a wide audience. He crafted a detailed theological framework that positioned Shabbatai at the center of a divine plan for redemption, linking traditional Jewish messianic expectations with Sabbatai's peculiar actions and declarations.

Nathan's writings and sermons spread rapidly, drawing a massive following and transforming Sabbatai from a relatively obscure kabbalist into a messianic figure with a significant religious movement behind him. His ability to convince others of Sabbatai’s divine role was a critical factor in the widespread acceptance and fervor of the Sabbatean movement across the Jewish diaspora.

Things get weird

A great deal of Tzvi’s appeal stemmed from his strange and bizarre behavior. In Judaism, there is an expectation that the Messiah must perform strange acts since these actions symbolize profound spiritual truths or serve to fulfill mystical prophecies in ways that transcend ordinary religious practices. This was especially true during the time of Sabbatai Tzvi, given the heavy influence of Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism, in the mainstream Jewish community. The Zohar, the central text of the Kabbalah, was reportedly better understood than the Talmud among Jews at the time.

In Kabbalistic thought, the Messiah's role involves a mystical redemption that transcends mere earthly salvation, aiming to repair cosmic imperfections and restore the divine harmony disrupted since the creation of the world. The messiah’s bizarre acts are seen as tests of faith or as ways to catalyze spiritual awakening and transformation among the people, signaling the advent of a new, redemptive era.

One of the most profound aspects of Sabbatai Tzvi’s messianic persona was his tendency to experience and publicly display extreme mood swings, which he and his followers interpreted as manifestations of spiritual ecstasy and divine inspiration. These episodes were often accompanied by prophetic utterances and mystical interpretations of religious texts that broke from traditional Jewish norms. Additionally, Sabbatai Tzvi declared certain fast days as occasions for feasting, reversing established religious practices, which he claimed was part of the messianic redemption process.

At one point, Tzvi married a Torah scroll (I wonder who catered) and declared some mainstream music at the time to be of the highest religious nature. This is the equivalent of a powerful rabbi saying Taylor Swift’s music should now be sung in religious ceremonies. These strange acts and declarations contributed significantly to the fervor and controversy surrounding his messianic claims.

In a remarkably short time, Tzvi and Nathan of Gaza had convinced the majority of the Jewish world that he was the Messiah and it was time to move to Jerusalem. Across Europe, Jewish communities began selling their belongings and moving to Palestine. This caused significant concern among Ottoman authorities, who controlled the Eastern Mediterranean and Palestine.

Indeed, Tzvi’s claim to messiahship faced a critical challenge in 1666 when he was arrested by the Ottoman authorities. In a meeting with the Sultan in Constantinople, he was given the choice to convert to Islam or die. He chose Islam. His conversion devastated his followers and splintered his movement. Some of his most devoted adherents continued to believe in him, asserting that his conversion was a part of a divine plan and a necessary act of mystical abasement according to certain interpretations of Kabbalah.

In one unique interpretation of Jewish mysticism, some followers believed that Sabbatai Tzvi's apostasy was a deliberate act meant to reclaim "sparks" of divinity hidden within other religions. This idea is rooted in the Kabbalistic concept of tikkun olam, which translates to "repairing the world." Tikkun olam suggests that divine sparks were scattered throughout the world at the time of creation, and humanity's mission is to gather these sparks to restore the world's original divine harmony, thus hastening redemption.

The rest of the Jewish community, however, burned records of Sabbatai Tzvi, attempted to erase the memory of the episode, and moved on with their lives. It’s been argued the rise of Hasidic Judaism is partly rooted in the reaction to Sabbatai Tzvi's apostasy. Hasidic Judaism, which emerged in the 18th century, focuses on personal spirituality and a direct, individual connection to the divine. This emphasis on personal redemption and the spiritual potential of every individual can be seen as a response to the disillusionment caused by Tzvi’s apostasy. After the widespread disappointment in Sabbatai Tzvi's failed messianism, Hasidism offered a way to rediscover spiritual intensity and purpose without the immediate need for a messianic figure.

Essentially, Hasidism redirected the messianic yearnings towards personal spiritual development, promoting the idea that while the community waits for the messiah, each individual can foster a redemptive relationship with God. This perspective allowed for a deeply personal form of religious experience that contrasted with the communal disillusionment of the Sabbatean debacle. As for Sabbatai Tzvi, he led a marginal life after his conversion and died in obscurity in 1676.

Detour: The Donme

The Dönme were a group of Sabbatai Tzvi’s followers who converted to Islam along with him in 1666 but secretly retained certain aspects of their Jewish faith and practices. Instead of fully assimilating into Muslim society, they formed a distinct religious group. The Dönme maintained a secretive religious identity that blended Islamic and Sabbatean practices. They recognized Sabbatai Tzvi as the Messiah and continued to believe in his messianic role, incorporating this belief into a syncretic theological framework. Their religious practices included Jewish rituals performed in secret, and they developed a unique liturgy in Ladino that reflected their hybrid beliefs.

The Dönme community was tightly knit, largely endogamous, and secretive about their religious practices to avoid persecution. They were often well-educated and became influential in business, academia, and later in political spheres within the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. Many of Turkey’s leading newspapers today were founded by Dönme families. Their ability to navigate between Muslim and Jewish identities allowed them a certain degree of social and economic mobility.

Over the centuries, the Dönme played a significant role in the intellectual and political life of the regions they inhabited, particularly in the city of Salonica (now Thessaloniki, Greece), which was part of the Ottoman Empire. Their influence continued into the early years of the Turkish Republic, where some sources claim they were deeply involved in the Young Turk movement. There is a longstanding conspiracy theory in Turkey that Ataturk himself was a Dönme. The Dönme remain in Turkey today (you can even hang out with them!). When I lived there in 2013-14, I did a radio piece about their ongoing presence in Istanbul. While the community is small, the Dönme remain a popular topic for conspiracy theorists in Turkey.

Back to the Rabbi

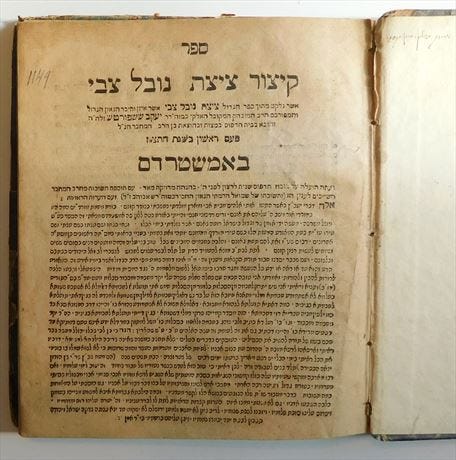

While the overwhelming majority of Jews at the time of Sabbatai Tzvi accepted him as the Messiah, there were a few critics. Rabbi Jacob Sasportas (1610-98) was a prominent Sephardic rabbi and one of the most vocal critics of the Sabbatean movement. Born in Oran, Algeria, Sasportas received his rabbinical education in Morocco. He served in various rabbinical positions across the Jewish communities of North Africa and later in Europe, including in key Sephardi communities in Amsterdam and Hamburg. His experiences in these diverse Jewish communities helped him develop a broad understanding of Jewish law and custom, which he later applied in his critiques of Sabbateanism.

As the Sabbatean movement gained momentum, Sasportas was alarmed by the widespread acceptance of Sabbatai Tzvi as the Messiah, which he viewed as delusional and dangerous to the fabric of Jewish life and law. In 1666, following Sabbatai Tzvi's apostasy and conversion to Islam, Sasportas's opposition found a new justification. He argued that Tzvi's conversion proved that he was a false messiah and that his followers were grievously misled. Sasportas's critiques were theological and concerned with maintaining community integrity and halachic observance amidst the disruption caused by messianic excitement.

Sasportas's most significant work is the Tzitzat Novel Tzvi (Blossom of the Strange Plant), a detailed account and critique of the Sabbatean movement. He compiled letters, testimonials, and observations, providing a contemporaneous account of the events and his arguments against the movement. Sasportas's legacy lies in his vigorous defense of traditional rabbinic Judaism against what he perceived as heretical innovations. His work is often studied in the context of Jewish responses to false messianism. It provides a crucial perspective for understanding the dynamics within the Jewish communities affected by the Sabbatean crisis.

The durability of the messianic idea

Reading Sasportas today, one can’t help but think about the messianism of our times. Zionism can be seen as one of the dominant messianic movements of contemporary Jewry insofar as it embodies a secular, nationalistic interpretation of the ancient Jewish hope for redemption through the return to and restoration of the homeland in Israel.

Arising in the late 19th century, largely as a secular movement, Zionism was a nationalist response to European antisemitism and the lack of a national homeland for Jews. Theodor Herzl and other Zionist leaders sought to establish a secure and sovereign Jewish state in the historic Land of Israel through political, social, and economic efforts rather than through divine intervention.

Although primarily political and practical rather than religious, Zionism shares with religious messianism the deep-rooted aspiration for Jewish renewal and sovereignty, echoing the prophetic promises of restoration and peace in the Land of Israel. However, there are vital departure points from normative Judaism. Messianism in Judaism traditionally holds that the Messiah will inaugurate an era of global peace and divine justice, including restoring a sovereign Jewish state centered in Jerusalem. The Zionist movement attempts to do this without a messiah, and that’s why some ultra-Orthodox communities refer to Zionism as a new form of Sabbateanism since the messiah has not come yet.

Both Sabbateanism and Zionism focus on the theme of redemption. Sabbateanism through a messianic figure and Zionism through self-determination and national revival (it’s debatable if these attempts have been realized meaningfully). Both of these movements arose in response to particularly intense persecution and instability faced by Jews (The Spanish expulsion and the Holocaust). They offered a form of hope and a plan for improving the plight of Jews.

Let me be clear: Sabbateanism and Zionism are fundamentally different in their approach and ideology, but they are both part of a broader narrative of Jewish attempts to cope with despair and envision a future of safety and prosperity. These movements highlight how Jewish history continues to)navigate between spiritual and secular solutions to existential threats and the question of Jewish emancipation in the West. This final point deserves a piece by itself. In place of such a piece, see Paths of Emancipation for a more robust discussion.

What would Sasportas have to say?

Given his conservative approach to Jewish law and tradition, as well as his critical stance towards messianic movements during his lifetime, one would assume that Sasportas would view Zionism in a harsh manner. He was a staunch defender of traditional rabbinic authority and the religious foundations of Jewish life. Modern political Zionism, especially in its early forms, was largely a secular movement focused on the political and cultural reestablishment of a Jewish homeland. Sasportas might have been skeptical of a movement that, in its origins, did not prioritize religious observance and was led by secular figures.

Moreover, Sasportas lived when Jewish identity was deeply intertwined with religious observance and less with nationalistic aspirations. He might question the shift towards a nationalistic interpretation of Jewish identity that underpins much of Zionist ideology. He was critical of any claims to immediate messianic redemption that bypassed traditional Jewish eschatological expectations.

Zionism’s early leaders did not claim to be messiahs, but the movement did aim to achieve some of the Jewish people's messianic hopes, such as the return to Zion and the restoration of a Jewish state. Thus, Sasportas might critique this aspect of Zionism as presumptuous or usurping the role traditionally ascribed to divine intervention. This is the position of many ultra-Orthodox communities around the world, including some in Israel.

On the other hand, given the historical events of the 20th century, especially the Holocaust and the profound impact it had on Jewish life and the global perception of the need for a Jewish state, Sasportas might recognize a practical necessity of a political solution to secure Jewish safety and continuity. He could be further compelled by the religious Zionist movement, which seeks to integrate Zionism with religious observance and sees the establishment of the state of Israel as part of a divine plan. Sasportas's response would likely involve a critical engagement with Zionism, weighing his deep commitment to religious tradition and law against the contemporary realities faced by the Jewish people.

What’s the point?

In this time of turmoil within the Jewish community, it's crucial to recognize that our challenges are not without precedent. As I watch cherished friends and family suspending their critical faculties to defend the indefensible, I'm reminded once again that the politics of messianism are inherently complex and fraught. And that’s some of what we are grappling with here … the politics of messianism. History shows us that fervor can cloud judgment, turning debates into battlegrounds. It's a cycle seen across centuries, urging us to approach contemporary issues with a historical perspective and a commitment to thoughtful dialogue. Shew, that was a long post. I might take next week off. Thanks for sticking around.